It’s not often that stepping indoors makes you feel more connected to the outdoors. I experienced this while viewing the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University’s new exhibition Spirit in the Land. The contemporary exhibition highlights the works of 30 present-day artists exploring the connections between artistic practice, climate change, people, nature, biodiversity, social justice, climate justice, and diversity. Director of the museum and curator of the exhibition Trevor Schoonmaker, in conjunction with the exhibition’s opening, said “Our desire to live in harmony with nature is ultimately what will determine our future.” This hauntingly beautiful quote coincides with a sense of beauty—and warning—this exhibition achieves. The dichotomy between harmony and tragedy present in this show begs the viewer to wake up and pay attention to the outside world around. And really, the works speak for themselves.

Here are a few of my favorites, toeing the line between beauty and tragedy:

Dario Robleto's The Naturalist's Lament, 2017

Despite its paper quality, there’s something oceanic about The Naturalist’s Lament—and it's not by accident. The laborious mixed-media work displays a variety of arranged seashells, marine-life imagery, and coral-like paper objects. “Robleto’s vision suggests that science cannot do it alone and presents us with an original framework for reimagining the beauty and possibility of the natural world and life as we know it.” And, while 71% of the world’s surface is water-covered, the sea is a crucial component in the climate change conversation. Robleto’s work offers a much needed oceanic perspective to this exhibition.

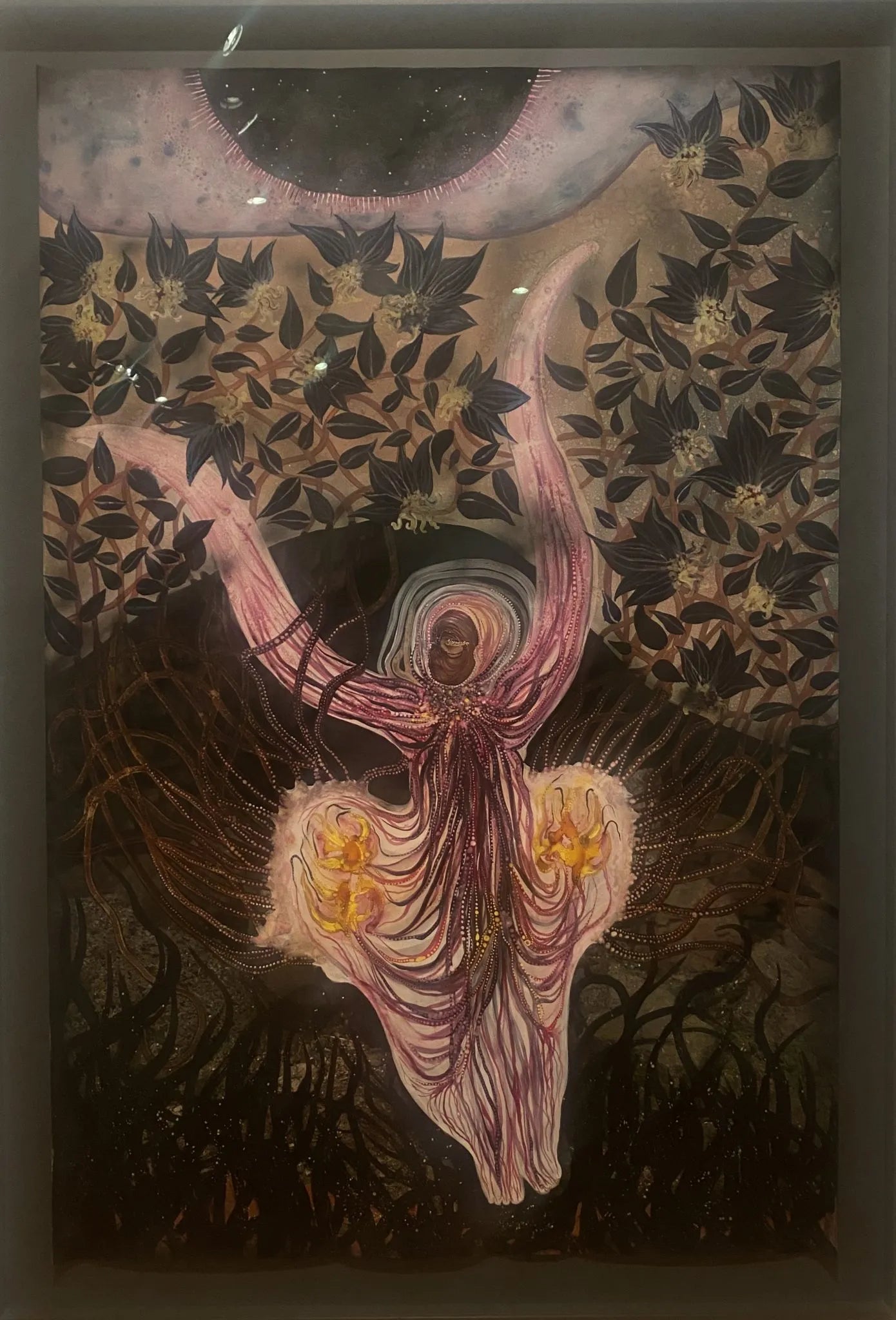

Wangechi Mutu Subterranea Flourish, 2021

Comfort and healing came to mind when I first laid eyes on Subterranea Flourish. Crafted from red clay, wooden roots, and cow horns, this work “depicts a part human, part plant being, rising from beneath the earth amidst a proliferation of roots, stems, leaves and flowers.” This work of art continues to explore Mutu’s understanding of nature as connected with all walks of life.

Alexa Kleinbard, Mayapple and Senna, Arnica, and Passion Flower from the series REMEDIES, 2003-2008

Mayapple and Senna, Arnica, and Passion Flower feel like windows into unknown worlds, glimpses into newfound places. The wreath-like floral structures hold medicinal plants and call to pollinating wildlife like butterflies, bees, frogs, and birds. According to the artist's statement on the exhibition wall label, the “series was inspired by my long-term exploration of folklore and medicinal recipes from indigenous peoples, of the physical and psychological healing properties that plants have given generously throughout time which must be protected.”

Christi Belcourt, This Painting is a Mirror, 2012

According to the exhibition wall label, Belcourt’s breathtaking work is based on the floral beadwork of Metis artists. By placing these thousands of dots on the canvas, Belcourt connects with her Indigenous Metis heritage by replicating a sacred form of beadwork. The title of the work, This Painting is a Mirror, comes from the idea that the beauty of the natural world is within each viewer, and the potential we have to use this connection to our advantage—according to the artist, “nothing is separate from anything else.” And she is right.

Maria Berrio, Hummingbird Series, 2021

Throughout the pandemic, Berrio created one mixed-media hummingbird every day. According to the artist, it became a therapeutic form of art-making during an isolating time. Over time, the hummingbird began to reflect the state of the world that day. These hummingbirds are installed side by side, creating a sense of unity and hope.

I left the museum and stepped out to meet a 78-degree day in mid-February. Climate change is here. The exhibition reminds us that our climate crisis is real, in all its forms of expression. Visual arts are beginning to play a crucial role in the climate change conversation—and this exhibition exists as one of the first. Science and political efforts cannot do it alone. With that in mind, I took a breath of the 78-degree air, and with Spirit in the Land fresh on my mind, felt a wave of hope wash over me.

©ArtRKL™️ LLC 2021-2023. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. ArtRKL™️ and its underscore design indicate trademarks of ArtRKL™️ LLC and its subsidiaries.