Feature image: Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning at the opening of the fourth annual Guild Hall invitational via Dan's Papers

Why Artists Flocked to the Hamptons in the 20th Century

Long Island’s South Fork curves between ocean and bay, folding dunes, potato fields, and salt marshes into a single horizon. During the 1940s and 1950s, this geography provided painters with an escape from the crowded Manhattan studios. The shoreline supplied uninterrupted light, gentle humidity, and silence broken only by gull calls and distant lobster boats. Barns stood ready for conversion into workrooms, and cottages cost little in the years after the war. Artists sensed that a rural setting could foster large gestures and fresh color relationships, prompting a migration that reshaped American art.

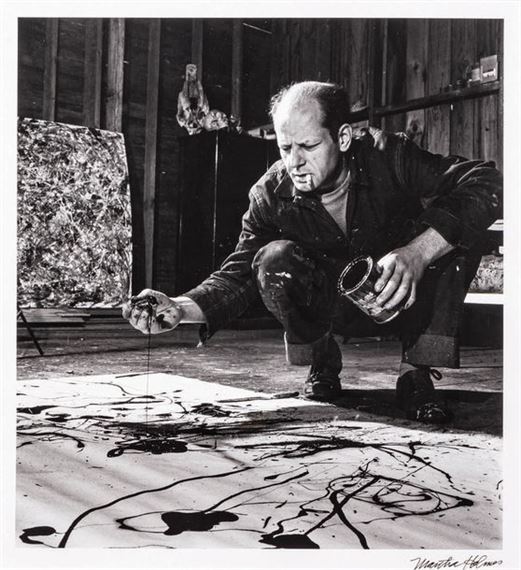

Pollock and Krasner: Rural Modernity

In 1945, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner purchased a cedar-shingled farmhouse in Springs with financial assistance from Peggy Guggenheim. Pollock spread unprimed canvas across the plank floor of a nearby barn and treated painting as a form of choreography. Works such as Autumn Rhythm and One: Number 31 absorbed the rhythm of wind-bent grass and tide-patterned sand. Krasner worked next door, often at night, producing swirling planes that echo the oak canopy around Accabonac Creek. The property now functions as a study center, and enamel drips still mark the floor, silent evidence of the moment when rural Long Island joined the vanguard of modernism.

A Network Gathers in Springs

Word of Pollock’s progress traveled through downtown loft circles and prompted peers to follow the same road east. Willem de Kooning settled near Louse Point, cycling each morning past fields fragrant with beach plum. Elaine de Kooning opened her cottage to poets, dancers, and critics, turning casual visits into vigorous debates about gesture, scale, and color temperature. James Brooks, Charlotte Park, and Joan Mitchell rented sheds or renovated chicken coops, lining walls with rolls of Belgian linen. Each painter absorbed the same light yet pursued a distinct vocabulary, confirming that place can nurture divergent methods.

Conditions That Supported Innovation

Several practical factors reinforced creative risk. The North Atlantic atmosphere delivered stable, cool illumination across entire days, allowing close study of pigment shifts. Barn floors accommodated canvases larger than any Manhattan elevator could carry, encouraging scale that matched ambition. Seasonal rents remained moderate through the early 1950s, channeling resources toward materials rather than overhead. Despite rural quiet, a three-hour drive returned finished work to Fifty-Seventh-Street dealers, sustaining vital market connections. The balance of solitude and access created conditions in which bold experimentation felt both desirable and sustainable.

Institutional Momentum on the East End

Cultural infrastructure developed alongside studio practice. Guild Hall in East Hampton organized annual juried exhibitions that introduced emerging painters to collectors vacationing along Further Lane. The Parrish Art Museum in Southampton broadened its program beyond American Impressionism, placing recent abstraction in dialogue with earlier landscape traditions. Weekend openings attracted critics, playwrights, and financiers whose presence amplified press coverage and stimulated sales. These institutions forged a feedback loop: Barn Studios generated daring canvases, museums provided platforms, and critical attention lured additional talent to the shore.

Evolution of the Scene in the Present Century

The Hamptons remain a cultural magnet, though the economic profile has shifted. International galleries maintain seasonal branches on the village's main streets. Hauser & Wirth curates focused summer installations, Pace presents intimate surveys, and Gagosian stages private viewings in discreet shingled properties. Collector culture exerts a visible influence. Summer residents install commanding works by Helen Frankenthaler, Rashid Johnson, or Cecily Brown above driftwood mantels, transforming guesthouses into micro-museums. Art fairs at Southampton Fairgrounds convene regional and global dealers each July, feeding an appetite for both historic abstraction and current experimentation.

Simultaneously, independent initiatives sustain community engagement. The Church in Sag Harbor, founded by April Gornik and Eric Fischl, is situated in a nineteenth-century Methodist sanctuary and features exhibitions, residencies, and lectures. LongHouse Reserve weaves sculpture by Buckminster Fuller, Yoko Ono, and Alice Aycock into botanical paths, merging environmental study with art historical inquiry. The Watermill Center, established by theater innovator Robert Wilson, offers interdisciplinary residencies where architects, choreographers, and sound artists test new proposals against the backdrop of a cedar forest and tidal flats. These ventures uphold the original ethos of the Hamptons, as both a retreat and a platform.

Collector Patronage and Market Gravity

High-profile collectors contribute contemporary momentum. Estates along Georgica Pond shelter troves that rival museum holdings, and gallery directors often schedule private tours among dune grasses and privet hedges. The presence of such collections encourages ambitious programming; artists debut large-scale painting cycles or outdoor installations confident that knowledgeable audiences will encounter them within a concentrated season. Academic researchers also benefit, gaining proximity to primary sources such as letters, sketches, and early states of significant works, preserved in local archives or private collections.

Landscape as Co-author

Every creative epoch on the East End draws directly from the environment. Early morning light filters through fog, rendering ultramarine shadows beneath cedar branches. Afternoon glare saturates cadmium orange, while beach stone and dune clay lend their chroma to earth-bound palettes. Salt particles carried inland by sea breeze settle on drying oil films, adding a subtle crystalline texture. Painters speak of sense memory: the crunch of shell fragments underfoot when stepping back from a canvas, the hum of cicadas marking intervals between brushstrokes. Landscape supplies impulse, texture, and cyclical rhythm, functioning less as a backdrop and more as an active collaborator.

The Hamptons demonstrate how geography, community, and institutional support can intersect to propel artistic evolution. Mid-century painters sought light and freedom, found both in rural barns, and unfolded methods that defined Abstract Expressionism. Successive generations adapt the formula: they arrive for atmosphere, encounter conversation, and leave transformed. Galleries, museums, and residencies continue to reinforce a cycle in which the environment shapes practice, and in turn, practice reshapes cultural identity. As evening glow settles over Accabonac Creek and studio windows gleam across open fields, the East End offers a living lesson in the capacity of place to sustain imaginative courage.

©ArtRKL® LLC 2021-2025. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. ArtRKL® and its underscore design indicate trademarks of ArtRKL® LLC and its subsidiaries.

All archival images in this article are used under fair use for educational and non-commercial purposes. Proper credit has been given to photographers, archives, and original sources where known.