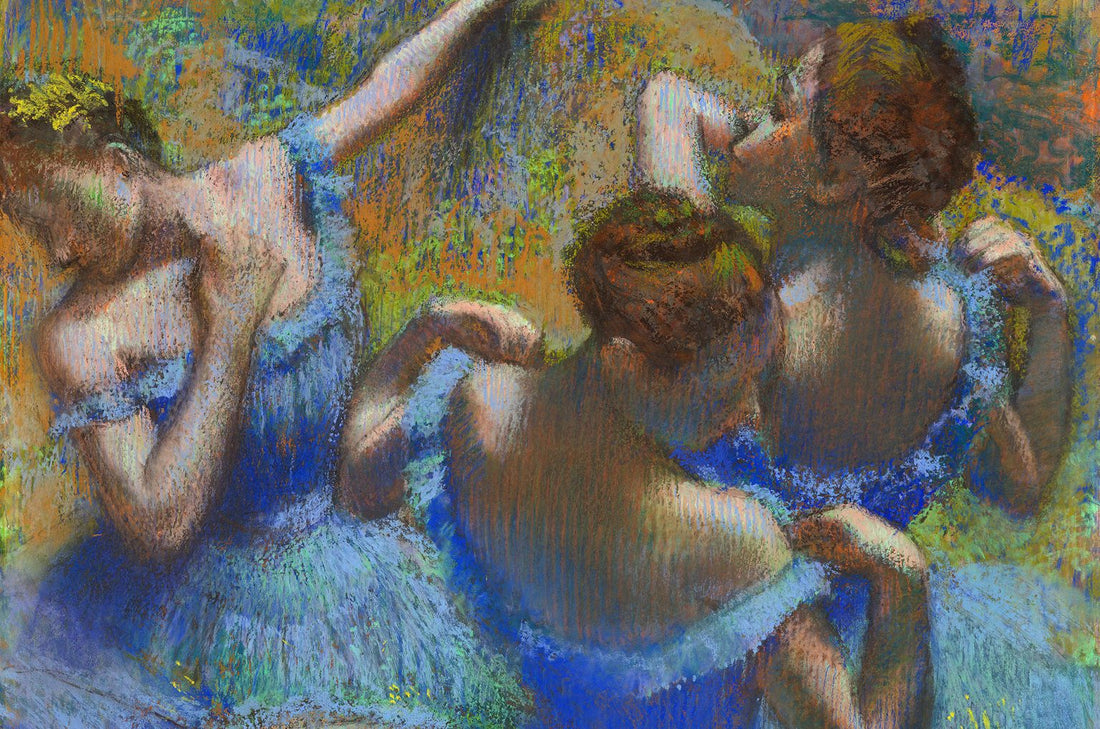

Feature image: Edgar Degas, Blue Dancers, 1899, Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia. Detail

Degas' Ballerinas

Like many young girls who grew up in the Chicago suburbs, I first encountered Edgar Degas’ ballerinas on a school field trip to the Art Institute of Chicago. My AP art history teacher was an eccentric woman who prided herself on the ability to challenge the notions of our unmolded, young, sheltered minds. Bringing us on a field trip to the Art Institute must have been like her own personal form of protest, an opportunity to show us how to “stick it to the man.”

Not that the Art Institute is a particularly political place in nature on the surface, but I admire her tenacity to want to open our worldview in whatever school-approved way she could. As our group made our way through the echoing halls of the museum, she continued to spout her ramblings on the pitfalls of creativity and character and the moralities behind the canvases before us. Like many 17-year-olds, though a field trip was of some intrigue, it ultimately was just an excuse not to be in school.

My mind strayed from her voice as I took in the framed pieces around me apathetically. As we entered the impressionism wing, I noted the painting featured in “Ferris Bueller's Day Off” and the famous piece of Van Gough’s bedroom. We weaved through the Friday morning tourist crowds to find ourselves in the front room of the impressionism wing. Among the many pastel, blurred images hanging on the walls was a painting of a ballerina with pale skin and a tangle of dark hair adorning a delicate pink and white tulle tutu and corset.

It is one of those images you see that fills you with a sense of whimsy and wonder upon initial viewing. While I have never had the stature to be a ballerina, I, like many other little girls, went through a phase where nothing was more romantic than ribbons on shoes and pirouettes. The painting plucked that perfect string of nostalgia and longing. This dream-like trance was suddenly broken by my AP art history teacher loudly saying the word “prostitutes” and pointing to the young ballerina in the painting. This sudden catapult back to reality quickly had me finally tuning in to her impassioned teachings.

“Each of these girls probably did sex work in addition to dancing; the Paris ballets were a feasting ground for rich men to pray on desperate girls,” she explained.

Looking back at the canvas, I no longer saw the romantic vision that had just captivated me. The image was soured. I did not see the exciting prospect of girls getting to live the dream I had also dreamed as a kid. Instead, I saw a bleaker reality, a sick image that, had I been born in another time, quickly could have been me.

It is estimated that Degas did over 1,500 paintings, sketches, and sculptures centered around the ballerinas of Paris. While it is common for artists to have particular motifs that appear over and over again in their works, there comes a time when fascination teeters on obsession. Degas falls into the latter, his paintings meticulously capturing dancers backstage, on stage, in rehearsal, and sometimes even in the arms of the wealthy patrons they had to serve.

While Degas is widely associated with the impressionists, he lauded himself as a realist instead. Perhaps realism was the only way to accurately articulate the solemn lives of the dancers he so feverishly captured daily. His leanings towards realism also make sense, given France's emerging school of realism at the time. With the stark change in life brought on by the consequences of the Industrial Revolution throughout Europe, the rose-colored tint so often used by the impressionist perhaps began to feel like more of a burden than a source of inspiration to Degas.

Yet, within his work, we still see this overarching sense of impressionistic style. From how the hazy stage lights capture the pleats in a tutu to the soft, fluffy hair of the dancers, Degas’ pension for impressionism is ultimately what made him so beloved as a painter, even with the scandalous subjects he portrayed. Let me clarify: Degas’ work was considered a major source of controversy during his time. The nature of the ballet was not some major secret to the people of Paris; it was well-known that the dancers often worked as escorts.

With this public knowledge, the fact that Degas often portrayed the ballerinas was a source of confusion, discomfort, and curiosity for many. It would be like if today an artist’s main line of work consisted of painting Onlyfans models. However, Degas did not care for the controversy surrounding his art; his main drive for wanting to paint the dancers was his obsession with the many forms he could capture in the light, movement, and figures of the ballerinas.

“People call me the painter of dancing girls,” Degas once explained to Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard. “It has never occurred to them that my chief interest in dancers lies in rendering movement and painting pretty clothes.”

Of course, it is worth mentioning that Degas had such freedom of controversy given his already affluent background. Even Degas’ friend Daniel Halvey noted Degas's extreme privilege and the limitlessness of his work.

“Their state of liberty is rare in the history of the arts, perhaps unique,” mused Halvey. “Never were artists freer in their researches.”

It is strange to me that Degas and I shared a similar love for the beauty of the ballet. That instinctively we both understood the captivating qualities of the elegant movement, softened lights, and girlish charm of the art. I do wonder how many of these girls Degas saw scurry into private rooms on the arms of men twice their age, or the saddened looks of girls who, despite doing everything they were told to do, still did not have enough money to support their family. Even after giving quite literally everything they could.

Dancing was one of the few ways girls could earn any type of income for themselves. It preyed on the young, impoverished girls who were desperate for ways to contribute to their family and to simply survive. Having to act as escorts in addition to dance was almost a given with the career path. After shows the dancers were paraded into the lobby and the wealthy patrons of the arts would approach. Getting in a good word from these rich donors not only resulted in better financial security, it could also give dancers larger roles in performances and more job security. The power imbalance of this relationship was glaring. It was said that girls who refused to engage in these post-show meetings often weren’t casted as frequently, and eventually fired.

The school of realism in art is often regarded as being one that is rather depressing. Capturing the realities of life, without the added flourish of emotion-based coloring or distortion of figures the images had to rely on the stark emotional value and narrative intrigue to articulate the artistic intent. I do think that there is something to be said about finding the value, and beauty in the mundane that is so key to understanding why realism seemed to pull in artists such as Degas.

In a poem written around 1889, Degas quipped, ““One knows that in your world / Queens are made of distance and greasepaint.”

I think Degas held a strong understanding of the world of the dancers he painted. On several occasions before he became a regular character at the ballet, he would use his affluent friends to find ways for him to get backstage or into the dressing rooms to observe the behind-the-scenes world of the dancer. Something I find fascinating was the fact Degas did not shy away from painting the wealthy patrons who flocked to the girls after the shows. Many of his works include the shadowy figure of men as they lurk in the stage wings, or surround a dancer post-show. The viewer is never explicitly told what is going on, but at the time of the creation of these pieces it would have easily been assumed.

I wonder how long it would have taken me to learn this same information had it not been for my mildly radical art history teacher? I teeter back and forth on the notion of if the paintings are meant to be somber, or if they are meant to be admirable. I suppose in the notion of realism neither are fully meant to be true. The images exist as Degas saw them, I doubt he felt a need to cast an explicit mood across the canvas. I wonder if the girls in these paintings could have ever imagined how admired and loved they are now? I wonder if they would see this as admiration, or, if to them this would simply be an extension of the gawking, lingering eyes they are already so familiar with.

During Degas’ time, the dancers were given the malicious societal nickname “petit rats,” translated to little rats. It could have been easy for Degas to amass a more welcomed artistic presence if he had not been so unwavering to his muses. Perhaps the greatest embarrassment brought on by this dedication was the incident surrounding his portrayal of a 14-year-old dancer.

Degas created a wax sculpture modeled after one of the girls; the statue was simply called “Dancer aged 14.” The statue was 39 inches tall and, when originally displayed, was fashioned with a human hair wig, tutu, ribbons, and more. Many made the unflattering comparison that it belonged in Madam Tussauds' gallery. People were appalled that Degas portrayed this girl so prominently and maliciously amused by the opportunity to continue the down-talking of these girls.

One art critic wrote, “Can art descend any lower?”

Art critic Paul Mantz scorned the piece, describing it as “flower of precocious depravity,” with a “face marked by the hateful promise of every vice.” He did not hold back in his brutal view of the girl. “With bestial effrontery,” he wrote, “she moves her face forward, or rather her little muzzle—and this word is completely correct because the little girl is the beginning of a rat.”

This statue ruined the girl whose likeness it portrayed. She was mocked, ostracized, and eventually forced to quit the ballet. Her very existence became a cruel joke, a singular target for the misogyny and classism people felt towards the ballerinas overall. Again, at just 14 years old, this girl was a public mockery target who now presumably had to take on sex work full-time to support herself because of her lost opportunity at the ballet.

Gazing upon Degas’ work carrying the information I do now, I feel a heavy sense of confusion. I am unsure how I am meant to view these pieces; my first instinct was to see the softened, romantic aspect of girlhood. For these pieces, in their own way, do capture girlhood. Beyond portraying the girls dancing, Degas shows them gossiping with their peers or being lost in daydreams. We are painfully reminded of just how old many of these dancers were. And that is where my confusion grows. It feels naive to look at these works without knowing the context and the history behind them. Now I am not saying these paintings need a giant red warning label screaming “PROSTITUTES” at anyone looking at them.

But I feel as if these images have been, in a sense, watered down to be palatable and digestible to a wider audience. Would patrons to the Art Institute of Chicago react similarly to the Parisians if we were in the know about the images we were seeing? I fear the answer to that may be yes. It very well may be a kinder remembrance to the legacy of these dancers to instead have people view them with a sense of awe.

©ArtRKL™️ LLC 2021-2024. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. ArtRKL™️ and its underscore design indicate trademarks of ArtRKL™️ LLC and its subsidiaries.