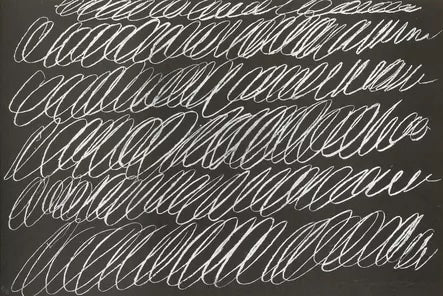

Feature image: Cy Twombly, 8 Odi di Orazio, 1968 via Artsy

Underrated Paintings by Cy Twombly You Should Know

Cy Twombly occupies a rare space in art history. His paintings sit between chaos and poetry, ancient myth and modern gesture. To some, his looping lines appear random or incomplete. To others, they feel like coded messages from another world. Twombly’s art rewards patience. His canvases are not meant to impress at first glance. They unfold slowly, revealing a rhythm of thought, memory, and touch that feels deeply human.

Although his monumental works like Leda and the Swan and Fifty Days at Iliam receive the most attention, Twombly’s quieter pieces hold equal significance. They trace his emotional life and his fascination with classical literature, history, and the written word. These paintings, often overlooked in favor of his more famous cycles, offer a glimpse into the artist’s most contemplative side.

Untitled (Bolsena), 1969

Painted during the summer of the Apollo 11 moon landing, Untitled (Bolsena) belongs to a series Twombly created while living near Lake Bolsena in Italy. The paintings reflect a moment of global anticipation, as humankind reached beyond the earth for the first time. Twombly’s gestures echo this sense of movement and expansion. Scribbles stretch across a luminous gray surface like orbits or gravitational paths. The lines feel alive, circling in silence.

The work captures both the precision of science and the poetry of discovery. Each mark balances control and spontaneity, mirroring the tension between structure and freedom that defined Twombly’s entire career. The paintings from this period connect the physical act of painting to the universal act of exploration.

Hero and Leander, 1985

In Hero and Leander, Twombly revisits a myth of love and loss. The story tells of Hero, a priestess, and Leander, her lover, who drowns while swimming across the Hellespont. Twombly’s painting transforms this ancient tale into a visual elegy. Words and fragments of text hover among expressive brushstrokes, as if the myth itself is dissolving into memory.

The canvas feels both emotional and intellectual. Layers of pale color and rough lines create the sensation of waves and wind. Twombly did not illustrate the story; he evoked it. The result feels like a dream of the myth rather than its depiction. The dripping paint becomes a form of mourning, a language of abstraction that replaces narrative with feeling.

Nini’s Painting (Rome), 1971

Nini’s Painting stands apart from Twombly’s mythic subjects. It was created in memory of a close friend, the Roman socialite Nini Pirandello. The painting carries a quiet tenderness that sets it apart from his more expansive works. A soft, luminous surface holds faint inscriptions and lines that seem to fade in and out of view. The palette feels mournful yet intimate, like a whisper of presence rather than absence.

This work reveals Twombly’s personal side. He rarely discussed his emotions publicly, preferring to hide behind mythological references. In Nini’s Painting, emotion is no longer masked. It becomes the subject itself. The painting feels like a letter written in code, one that expresses grief through restraint. Its stillness has a power equal to his largest canvases.

Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), 1994

Among Twombly’s late masterpieces, Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor remains one of his most ambitious and overlooked. The massive triptych, stretching nearly fifty-two feet, took more than a decade to complete. It combines his signature graffiti-like writing with vast fields of color and floating forms. The title refers to the Roman poet Catullus, who wrote of love, travel, and farewell.

The painting moves through stages of calm and turbulence. The viewer follows a flow of motion across the panels, like a long, handwritten sentence. Twombly’s soft blues and whites evoke sea foam and clouds, creating a sense of passage and memory. The work feels both epic and meditative. It acts as a visual farewell, a reflection on aging, distance, and the persistence of beauty.

Although the piece is monumental, it carries a sense of quiet reflection rather than grandeur. It distills Twombly’s lifelong themes into one fluid, lyrical statement. Every mark feels like the trace of a thought passing through time.

School of Athens, 1961

With School of Athens, Twombly connects himself directly to the history of Western art. The title recalls Raphael’s Renaissance fresco, but Twombly’s version replaces classical order with expressive energy. His marks dance across the surface, suggesting motion, debate, and intellectual exchange. The composition feels alive with conversation, like a chalkboard filled with fleeting ideas.

This painting represents Twombly’s deep respect for the ancient world. He saw classical thought as a living force rather than a fixed history. The scribbles resemble both handwriting and movement, implying that the act of thinking itself can be painted. Through this work, Twombly invites viewers to see knowledge as emotional and evolving, rather than static.

Untitled (Bacchus), 2005

In his later years, Cy Twombly returned to myth with a series that revolved around Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and ritual. Untitled (Bacchus) from 2005 is among his most powerful and least discussed late works. Large, looping red lines rush across a raw canvas, evoking both blood and celebration. The intensity feels physical, as if the paint itself is alive.

Although part of a wider Bacchus series, this particular work often goes unnoticed beside the more widely exhibited versions. Its force lies in its simplicity. The red spirals pulse with motion, suggesting both ecstasy and exhaustion. Twombly painted it in his eighties, yet the energy feels youthful. The repetition of gesture becomes an act of devotion, a meditation on vitality and mortality.

Untitled (Roses), 2008

Three years later, Twombly painted Untitled (Roses), a series of six large canvases inspired by the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke. The works shimmer with soft color and handwritten verses scrawled across their surfaces. Each rose feels more like a memory than a flower. The petals blur and dissolve, turning into gestures of thought and feeling.

One of the most overlooked paintings from this series combines pale pinks, golds, and creamy whites that drift across the canvas like clouds of pigment. Twombly’s inscriptions in pencil and crayon merge with the paint, creating a dialogue between word and image. The work radiates calm and reverence.

Unlike the Bacchus paintings, which celebrate frenzy, Untitled (Roses) conveys serenity. It feels like a quiet resolution after decades of searching. The subject of the rose, long associated with love, beauty, and death, became Twombly’s final meditation on art itself. Through this work, he achieved a harmony among abstraction, text, and poetry.

Why His Quiet Works Matter

In a century dominated by loud gestures and monumental statements, Twombly’s paintings whisper instead of shout. They remind us that art can speak through subtlety and restraint. His brushwork feels closer to writing than to traditional painting, transforming each surface into a space for reflection.

The overlooked pieces, such as Nini’s Painting or Untitled (Bolsena), show how deeply Twombly understood the relationship between time, memory, and the act of creation. His art bridges the past and present, linking mythology with modern emotion. To spend time with these works is to witness thought as a living process.

©ArtRKL® LLC 2021-2025. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. ArtRKL® and its underscore design indicate trademarks of ArtRKL® LLC and its subsidiaries.