Feature image: Klimt, Hope II, 1907-08 via Wikipedia

Where are the Pregnant Women in Art?

Women have, in abundance, been depicted as subjects in works of art throughout history and across cultures. However, especially within the Western tradition, representations of women have largely conformed to patriarchal gender norms—images of virginal, chaste, youthful, lily-white muses dominate historical themes of femininity. As such, it is rare to see departures from those themes, particularly those that depict women as strong and autonomous beings. Pregnancy is a prime example of a seldomly depicted artistic subject.

There are several possible explanations, cultural and practical, for the lack of depictions of pregnancy in art. First, pregnancy used to be far more fatal, so commissioning a painting of a pregnant woman would have been considered to be premature. Second, pregnancy has often been a taboo subject because of its association with sex. This is particularly true among patriarchal religious traditions that, as part of a larger system of men’s control over women’s bodies, hold “purity,” or abstinence from sex, as one of the most valuable and essential aspects of womanhood. These beliefs led many artists to avoid depicting women as pregnant, even if they were. Not even the Virgin Mary, revered among Christians as Mother of God, was exempt from this practice.

It should be noted that not all pregnant people identify as women, and while non-binary and trans individuals have always existed, they have not always been free to express themselves. For the majority of history, gender expression has been a strict code to which people are socially, emotionally, and, at times, physically forced to adhere. While this article speaks largely from a historical narrative and, as such, only refers to pregnant women, it is important to recognize that not all pregnant people are women.

1300s-1400s:

While the Virgin Mary’s immaculate pregnancy is considered a miracle in the Christian tradition, she very rarely is depicted as visibly pregnant, despite beliefs that she carried the Son of God in her womb. Religious painters of the Early European Renaissance often opted to bury Mary’s stomach under large skirts. This is the case in Rogier van der Weyden’s Visitation. Painted in 1445, this work depicts the pregnant Mary visiting her cousin Elizabeth, who, in biblical canon, was pregnant as well. The women touch each other's wombs, suggesting their pregnancies, but their stomachs remain shockingly flat for those who were supposedly carrying another human being. In fairness, Mary was only meant to be about one month pregnant at this time, but Elizabeth was thought to be seven months along. The absence of pregnant bellies was standard practice among artists during this time, but it did become popular to depict the Virgin Mary as pregnant in a few rural regions of Italy. These depictions are called ‘Madonna del Parto.’ Most of these works were destroyed in the counter-reformation of 1545, but a popular fresco painted by Piero della Francesca of ‘Madonna del Parto’ survived. In this work, two angels part curtains to reveal the Virgin Mary, who stands in a floor-length blue dress, resting her hand on her bulging belly.

1500s-1600s:

There was a rise in the popularity of portraits of pregnant women in the mid-1500s due largely to the Protestant belief that women were in their most holy state while pregnant. During this time, both the Virgin Mary and secular women were more frequently represented with overt bumps under their elegant dresses. Marx Reichlich reimagines the meeting between Mary and Elizabeth— this time, however, the women are both very clearly with child. In 1656, Carlo Maratta depicted Mary and Elizabeth in the same manner. Likewise, secular pregnancy portraits became popular during this time. Artist Marcus Gheeraets the Younger painted multiple portraits of women while they were pregnant. Well-known examples of this include Portrait of a Woman in Red, Portrait of an Unknown Lady, and Anne Fanshaw, First Wife of Thomas. In 1506, Raphael painted the work La Donna Gravida, and in 1634, Rembrandt created the work Portrait of Oopjen Coppit. Both works depict overtly pregnant women. Often, in these portraits, the women would gently rest a hand on their stomachs as a way to not only draw attention to their pregnant state but also act as a protective gesture toward their unborn child. By the 1700s, this trend of secular portraits depicting pregnant women fell away completely.

1700s-1800s:

Increasingly conservative attitudes and changes in visual tastes saw a shift away from depictions of pregnancy in the 1700s and 1800s. Historian Cynthia Northcutt Malone remarks, “For most of the nineteenth century, in the novel and in bourgeois culture, pregnancy was visible but unspeakable.” Accordingly,during this time advice books written by medical men used euphemisms to avoid direct references to pregnancy. While it was seen as a woman’s duty to bear children, the topic of pregnancy was viewed as taboo and offensive to discuss. Images of pregnant women were few and far between during this time. The one area in which pregnancy may have been depicted and discussed was through satirical prints. For example, a print by I. T. depicts a physician examining a urine sample belonging to an unmarried woman who is pregnant and is subsequently scolded by her mother. The faint outline of a baby can be seen floating in the urine sample. William Hogarth also illustrated a few comical scenes depicting pregnant women, including his work A Woman Swearing a Child to a Grave Citizen. These depictions did not celebrate or lend a positive light to a woman's pregnant state but rather showed pregnancy as the deserved result of sinful and promiscuous behavior.

1900s-Present:

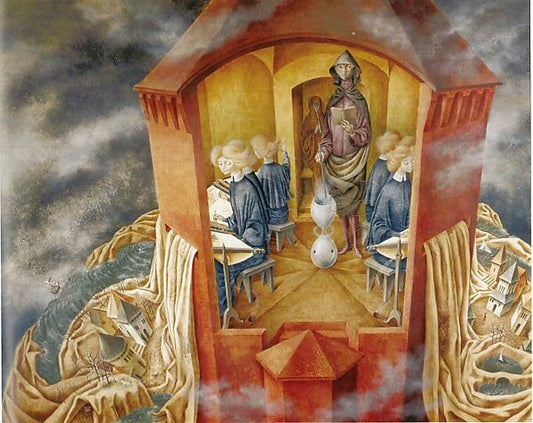

In the contemporary age, artists have taken to depicting themselves pregnant as a form of empowerment. Paula Modersohn-Becker is thought to be the first painter to depict herself pregnant in her 1907 work Self-Portrait with Two Flowers in her Raised Left Hand. Klimt famously painted two different works that focused on pregnant women in 1903 and 1908, both of which were received with contempt among conservative groups in Austria. These works, Hope i and Hope ii address the enigmatic cycle of life and death. Taboos surrounding pregnancy, having largely been left in the past, have allowed contemporary artists to portray pregnancy in a variety of ways—it is no longer depicted monolithically. Formal dress and grave, solemn poses have given way to far more casual and stylistic depictions of pregnancy. This can be easily observed in works such as Patrick George’s June in Bed. In this work, a pregnant woman lays on her side, resting comfortably in a fluffy bed wearing nothing but a sheer dress. She relaxes in what is presumably her bedroom with her eyes closed and her face full of peace.

Depictions of women in art, like representations of any kind, are reflections of and are in constant conversation with the historical moment from which they spring. In the same way, the appearance of pregnancy in art has cycled through various evolutions that mirror cultural views of what pregnancy is and how it relates to femininity in a more complete sense. In this current historical moment, artists envision an environment of liberation in which pregnancy is no longer viewed as taboo and unspeakable.

©ArtRKL™️ LLC 2021-2024. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. ArtRKL™️ and its underscore design indicate trademarks of ArtRKL™️ LLC and its subsidiaries.